The free will to make decisions is one of the most vital aspects of the human condition. We are constantly confronted with the forks in life’s path that each choice presents: Should I postpone writing this essay for another day, or start now even though I don’t feel inspired? Should I eat that leftover Big Mac in the fridge, or take the time to cook myself a healthy meal? Most importantly, it is the consistent decisions made over time that shape enduring habits — the ones that determine the trajectory of a person’s life.

I have developed a mental tactic that I find useful for cultivating and protecting positive habits. It involves contemplating the fourth dimension — time — and the countless replicas of myself it continuously creates and discards. The “me” from an hour ago, a week ago, four years ago; the “me” two weeks or ten years into the future, or even tomorrow. Each represents a different self, frozen in either the past or the future. The essential difference between them lies in the fact that the future can still be thawed and reshaped, while the past remains permanently sealed — existing only in memory, serving as a reservoir of lessons.

A single day is the caricature parti diagram* of an entire life. If we think about it, life itself could be viewed as a single day replicated under varying external conditions — for as long as our genes and environment allow. By focusing on the nucleus of life — the day in repetition — we begin to realize that a fulfilling existence requires one to act as a comprehensive planner of the day1. The conscious and subconscious parts of the mind can only work in harmony when the former is able to program the latter through habit and repetition. Each day is like a blank canvas upon which one may craft the art of living through deliberate planning and structure. What this plan comprises of depends entirely on one’s personal pursuits — but the only essential rule is that it must not be squandered through idleness or indolence. One should be able to fully adapt to a plan — to write it down and follow it — yet remain flexible enough to revise it as time passes and one’s pursuits inevitably evolve. But the plan must always exist, lingering in the back of the mind, quietly enforcing progress as the unrelenting passage of time takes its course. This way, one does not reach the age of fifty with a sense of shock — “My God, how quickly it all went by; I hardly remember anything.” Instead, one should be able to say, “I’m fifty now — as expected. It’s no surprise. So far, I’ve done well. Now it’s time to plan the remainder carefully, so that my accomplishments and joys may deepen, and life may not feel as though it has been wasted.”

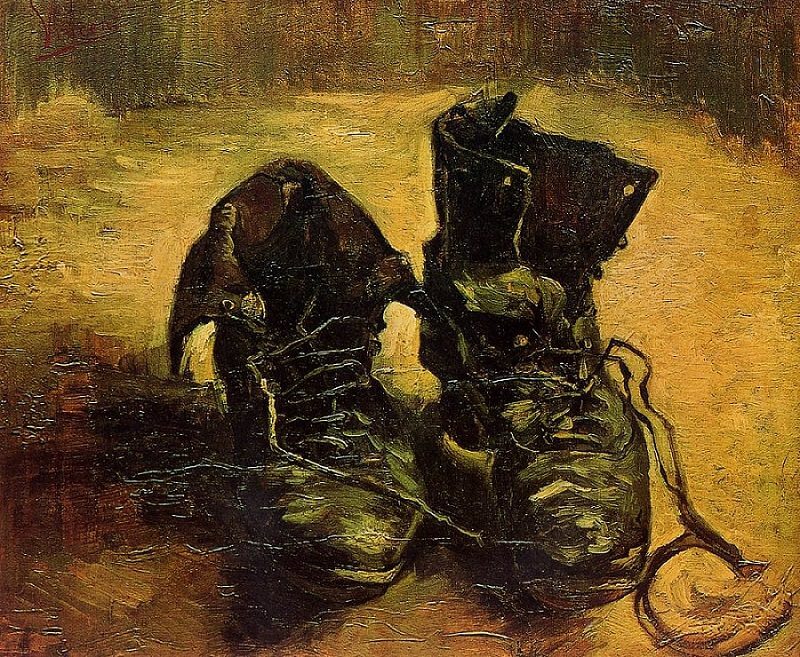

I chose the painting above by Marcel Duchamp, which depicts a figure descending a staircase through time, rendered according to modern Cubist principles, with multiple replicas of the same figure in motion. Painted and exhibited in 1912, this style was innovative and drew significant media attention at the time. While I am not particularly drawn to the philosophy behind the painting, I see it as a symbolic representation of the theme of this essay. I believe that certain visual cues in the mind can serve as powerful guides, helping one remain focused when applying long-term effort and discipline.

Continue reading