With its pragmatic architectural curriculum, as I was studying at the University of Maryland’s Architecture and Urban Design program (2006-2011), I have first heard about Walter Gropius and the Bauhaus movement from my mentors. Skimming through various picture books of Bauhaus products and buildings in the schools library, I ruled out using such precedents for my design projects due to its emphasis on the repetitive international/global style which I assumed it prioritized. However, as I read this book written by Gropius himself, to my surprise, my initial negative thoughts on the theoretical side of the Bauhaus formed during my studies were one by one proven wrong. It turns out that, Mr. Gropius, is in fact a region sensitive architect and writer who tends to be against an overarching omnipresent international style, and is, actually, quite displeased that his work had been interpreted by others as a international “style” in design.

After the Great war he took on to the daunting task of establishing the Bauhaus institution to engage context and circumstance appropriate meaning to the technological innovations in his field. His main aim being to utilize the apparently cold new industrial building technologies to serve a more humanist agenda through collaborative theoretical and craft/skill oriented design processes.

In his book he talks about the differences between handicraft and industry, where the latter utilizes methods of subdivision in labor as opposed to the undivided involvement of a single workman through out the whole process possible only in the prior.

I am particularly impressed with Mr. Gropius’ captivating writing style, which pulls his readers into the depths of his mind where the larger and long term picture of design is scrutinized. He presents his arguments with clarity and organization based on his empirical experiences in the field.

However, I must also note here that I was particularly disheartened when reading Chapter 11 with his enthusiasm on high-rise apartment buildings and his ruling out of urban fabric generating low rise buildings. The mathematics he puts into his arguments may be correct, however his earlier writings on the importance of beauty for instance betrays his view here on the ideal dwelling. Parallel apartment buildings with unlimited heights are clearly anti urban in their nature, and I must say I was disappointed to read his views on this topic. Regardless, it is a good book and I do recommend reading it.

Below are some excerpts I highlighted from the book with my attached corresponding notes below:

“…To sharpen this sense of balance and feeling for equipoise is something we all have to accomplish individually in our lives.

For instance, when we accuse technology and science of having deranged our previous concepts of beauty and the “good life,” we would do well to remember that it is not the bewildering profusion of technical mass-production machinery that is dictating the course of events, but the inertia or the alertness of our brain that gives or neglects to give direction to this development. For example, our generation has been guilty of producing horrors of repetitious housing developments, all done on a handicraft basis, which can easily compete in deadly uniformity with those ill-advised prefabrication systems which multiply the whole house instead of only its component parts. It is not the tool, it is our mind that is at fault. …”

Just because the technology is out there and available does not mean we ought to surrender ourselves to all of its capabilities. Instead we must sort out and select aspects from the avant-garde technologies in order to serve our interests in the “long run”.

“… I want to rip off at least one of the misleading labels that I and others have been decorated with. There is no such thing as an “International Style,” unless you want to speak of certain universal technical achievements in our period which belong to the intellectual equipment of every civilized nation, or unless you want to speak of those pale examples of what I call “applied archeology,” which you find among the public buildings from Moscow to Madrid to Washington. Steel or concrete skeletons, ribbon windows, slabs cantilevered or wings hovering on stilts are but impersonal contemporary means—the raw stuff, so to speak—with which regionally different architectural manifestations can be created. The constructive achievements of the Gothic period-its vaults, arches, buttresses and pinnacles-similarly became a common international experience. Yet, what a great regional variety of architectural expression has resulted from it in the different countries!

As to my practice, when I built my first house in the U.S.A., which was my own—I made it a point to absorb into my own conception those features of the New England architectural tradition that I found still alive and adequate. This fusion of the regional spirit with a contemporary approach to design produced a house that I would never have built in Europe with its entirely different climatic, technical and psychological back-ground. …”

Mr. Gropius is annoyed by the fact that those who have not really scrutinized his writings and architectural work have opted to simply generalize his efforts with the Bauhaus as an attempt to initiate a new type of international movement in optical style. Furthermore, He talks about the regional characteristics of the architecture of his house in New England, to further his claims on not looking to establish a new copy paste-able international style regardless of physical and cultural context.

“… I have sometimes felt a certain disappointment at being asked only for the facts and tricks in my work when my interest was in handing on my basic experiences and underlying methods.

In learning the facts and tricks, some can obtain sure results in a comparatively short time, of course; but these results are superficial and unsatisfactory because they still leave the student helpless if he is faced with a new and unexpected situation. If he has not been trained to get an insight into organic development no skillful addition of modern motives, however elaborate, will enable him to do creative work. …”

On the importance of understanding the process and inner mechanics of art creation and composition as opposed to analyzing and emulating the final end product.

“… My ideas have often been interpreted as the peak of rationalization and mechanization. This gives quite a wrong picture of my endeavors. I have always emphasized that the other aspect, the satisfaction of the human soul, is just as important as the material, and that the achievement of a new spatial vision means more than structural economy and functional perfection. The slogan “fitness for purpose equals beauty” is only half true. When do we call a human face beautiful? Every face is fit for purpose in its parts, but only perfect proportions and colors in a well-balanced harmony deserve that title of honor: beautiful. Just the same is true in architecture. Only perfect harmony in its technical functions as well as in its proportions can result in beauty. That makes our task so manifold and complex. …”

Mr.Gropius sheds light on the incompleteness of the famously used theory: form follows function. He proposes, instead, that form and function may alternate in following each other based on circumstance and endeavor. There are certain aspects of design where 2+2 may not necessarily equal 4 as one may calculate based on mathematical logic, indeed, sometimes it may equal 5, sometimes 8, and sometimes, perhaps even 2,01. To make this calculation one’s artistic faculties must be fully functional and alive.

“… The craftsman, on the other hand, with the passing of time began to show only a faint resemblance to the vigorous and independent representative of medieval culture who had been in full command of the whole production of his time and who had been a technician, an artist and a merchant combined.

His workshop turned into a shop, the working process slipped out of his hand and the craftsman became a merchant. The complete individual, bereaved of the creative part of his work, thus degenerated into a partial being. His ability to train and instruct his disciples began to vanish and the young apprentices gradually moved into factories. There they found themselves surrounded by meaningless mechanization which blunted their creative instincts, and their pleasure in their own work; their inclination to learn disappeared rapidly. …”

In a way, what happened to the arts and crafts in the early 20th century with the advancement of industrialization could be analogous to what the technological innovations with Artificial Intelligence today is doing to industries. Many in the field of construction fantasize about a possible doomsday for architects as they are gradually replaced by the advancing self governing intelligent technologies, however the issue may be more of a need to adapt than to re-consider such professions. I personally have no faith in an ‘artificial’ intelligence devoid of emotion to surpass the human mind in the arts. There are many aspects of the un replicable human experience, which affect our designing capabilities, for instance, the ability to compositionaly adapt a project despite its changing nature. In a way, the ability to turn the obviously unfortunate into fortunate, by positive thinking via emotional fortitude.

The main problem will be to discover the most effective way of distributing the creative energies in the organization as a whole. The intelligent craftsman of the past will in future become responsible for the speculative preliminary work in the production of industrial goods. Instead of being forced into mechanical machine work, his abilities must be used for laboratory and tool-making work and fused with the industry into a new working unit. At present the young artisan is, for economic reasons, forced either to descend to the level of a factory hand in industry or to become an organ for carrying into effect the platonic ideas of others; i.e., of the artist-designer. In no case does he any longer solve a problem of his own. With the help of the artist he produces goods with merely decorative nuances of new taste which, although associated with a sense of quality, lack any deep-rooted progress in the structural development, born of a knowledge of the new means of production.

What, then, must we do to give the rising generation a more promising approach to their future profession as designers, craftsmen or architects? What training establishments must we create in order to be able to sift out the artistically gifted person and fit him by extensive manual and mental training for independent creative work within the industrial production?

Only in very isolated cases have training schools been established with the aim of turning out this new type of worker who is able to combine the qualities of an artist, a technician and a businessman. One of the attempts to regain contact with production and to train young students both for handwork and for machine work, and as designers at the same time, was made by the Bauhaus.

The problem of new industries dulling emerging young talents, appropriating them into mass production jobs.

“… The fact that the man of today is, from the outset, left too much to traditional specialized training—which merely imparts to him a specialized knowledge, but does not make clear to him the meaning and purport of his work, nor the relationship in which he stands to the world at large was counteracted at the Bauhaus by putting at the beginning of its training not the “trade” but the “human being” in his natural readiness to grasp life as a whole. …”

The importance of keeping the larger picture in mind as well as having command over the details.

“… the “complete being” who, from his biological center, could approach all things of life with instinctive certainty and would no longer be taken unawares by the rush and convulsion of our “Mechanical Age.” The objection that, in this world of industrial economy, such a general training implies extravagance or a loss of time does not, to my mind and experience, hold good. On the contrary, I have been able to observe that it not only gave the pupil greater confidence, but also considerably enhanced the productiveness and speed of his subsequent specialized training. Only when an understanding of the interrelationship of the phenomena of the world around him is awakened at an early age will he be able to incorporate his own personal share in the creative work of his time. …”

On the importance of seeing the big picture and well-roundedness as one works on the details of his craft.

“… In the course of his training, each student of the Bauhaus had to enter a workshop of his own choice, after having completed the preliminary course. There he studied simultaneously under two masters-one a handicraft master, and the other a master of design. This idea of starting with two different groups of teachers was a necessity, because neither artists possessing sufficient technical knowledge nor craftsmen endowed with sufficient imagination for artistic prob-lems, who could have been made the leaders of the working departments, were to be found. A new generation capable of combining both these attributes had first to be trained. In later years, the Bauhaus succeeded in placing as masters in charge of the workshops former students who were then equipped with such equivalent technical and artistic experience that the separation of the staff into masters of form and masters of technique was found to be superfluous. …”

Here Gropius mentions the ideal graduate of Bauhaus as one who is in command of both the theoretical and technical sides of their field. Theory and craftsmanship ought never be disengaged, or else, it would be like talking a lot without saying anything. Aren’t we all tired of such people ?

“… In its collaboration with industry, the Bauhaus attached special importance also to bringing the students into closer touch with economic problems. I am opposed to the erroneous view that the artistic abilities of a student may suffer by sharpening the sense of economy, time, money and material consumption.

Obviously it is essential clearly to differentiate between the unrestricted work in a laboratory on which strict time limits can hardly be imposed, and work which has been ordered for completion at a certain date; that is to say, between the creative process of inventing a model and the technical process involved in its mass production. Creative ideas cannot be made to order, but the inventor of a model must nevertheless develop trained judgment of an economic method of subsequently manufacturing his model on mass production lines, even though time and consumption of material play only a subordinate part in the design and execution of the model itself. …”

Unlimited time and funds do not necessarily mean an exceptional outcome in the product. Contrarily, limited material availability and time may actually create an elevated level of discipline in the mind of an artist. Constraints ought to be welcomed into a design project. Take a look at today’s digitized generation with unlimited internet and options for learning. Too many options and a comfortable budget may actually create an undesirable effect on the artist, causing him to be overwhelmed by options and freedom in time, similar to attempting to drink water from a fire hydrant. One needs to have an extra level of discipline when working in today’s world of distractions and abundance.

“… In particular, the erection of our own institute buildings, in which the whole Bauhaus and its workshops co-operated, represented an ideal task. The demonstration of all kinds of new models made in our workshops, which we were able to show in practical use in the building, so thoroughly convinced manufacturers that they entered into royalty contracts with the Bauhaus which, as the turnover increased, proved a valuable source of revenue to the latter. The institution of obligatory practical work simultaneously afforded the possibility of paying students- even during their three years of training-for salable articles and models which they had worked out. This provided many a capable student with some means of existence. …”

Students in the bauhaus were not in an isolated world with minimum real-time market contact, as seen in the today’s Universities. Their ideas were constantly put to the test. As possible investors seeking an opportunity to profit constantly circled around the bauhaus facilities, material rewards and incentives were always on the table.

The most essential factor of the Bauhaus work was the fact that, with the passing of time, a certain homogeneity was evolved in all products: this came about as the result of the consciously developed spirit of collaborative work, and also in spite of the co-operation of the most divergent personalities and individuali-ties. It was not based on external stylistic features, but rather on the effort to design things simply and truthfully in accordance with their intrinsic laws. The shapes which its products have assumed are therefore not a new fashion, but the result of clear reflection and innumerable processes of thought and work in a technical, economic and form-giving direction. The individual alone cannot attain this goal; only the collaboration of many can succeed in finding solutions which transcend the individual aspect-which will retain their validity for many years to come.

Surprisingly, despite the diverse profile of student and master backgrounds in the Bauhaus, the outcome of all the designed products had a visually discernible repetitive theme in form. Mr. Gropius justifies the reason for this outcome as the collaborative nature of forming a common sense aesthetic constantly edited by economical, cultural, technological, sociological and political restrictions.

“… The success of any idea depends upon the personal attributes of those responsible for carrying it out. The selection of the right teacher is the decisive factor in the results obtained by a training institute. Their personal attributes as men play an even more decisive part than their technical knowledge and ability, for it is upon the personal characteristics of the master that the success of fruitful collaboration with youth primarily depends. If men of outstanding artistic ability are to be won for an institute, they must from the outset be afforded wide possibilities for their own further development by giving them time and space for private work. …”

The profile of teachers is the single deciding factor of that institutions success. You could have the best most talented students but if the leadership is flawed the results will follow. However, if the leadership and teachers are made out of a determined, skilled and ambitious profile, even the mediocre student, if tuned in to the work, would excel.

“…The ability to draw is all too frequently confused with the ability to produce creative design. Like dexterity in handicrafts, it is, however, no more than a skill, a valuable means of expressing spatial ideas. Virtuosity in drawing and handicrafts is not art. …”

Just because one can draw artistically well, does not mean he could be a good designer. Designing is a thought process, more akin to composing a musical composition or a well written essay.

“… If we can understand the nature of what we see and the way we perceive it, then we will know more about the potential influence of man-made design on human feeling and thinking. …”

An analytical system in which we may understand the general effects of design on people.

“… The initial task of a design teacher should be to free the student from his intellectual frustration by encouraging him to trust his own subconscious reac-tions, and to try to restore the unprejudiced receptivity of his childhood. He then must guide him in the process of eradication of tenacious prejudices and relapses into imitative action by helping him to find a common denominator of expression developed from his own observation and experience. …”

Methods for letting students prosper in their own natural directions, as opposed to wanting to create a mini-me version of ourselves through the work of students.

“… If design is to be a specific language of communication for the expression of subconscious sensations, then it must have its own elementary codes of scale, form and color. It needs its own grammar of composition to integrate these elementary codes into messages which, expressed through the senses, link man to man even closer than do words. The more this visual language of communication is spread, the better will be the common understanding. …”

The need for clear graphic conventions for communicating design ideas as opposed to complete freedom in graphic representation.

“… THE NEED FOR CHANGE. This shift in the basic concept of our world from static space to continuously changing relations engages our mental and emotional faculties of perception. Non we understand the endeavors of Futurists and Cubists who first tried to seize the magic of the fourth dimension of ting by depicting motion in space (Fig. 29). In a picture by Picasso the profile and front of a face are depicted; a sequence of aspects is shown simultaneously (Fig. 30). Why? This element of time, apparent in modern art and design, evidently increas the intensity of the spectator’s reactions. The designer and the artist seek to create new and stimulating sensations which will make us more receptive and more active. This statement corresponds with Sigmund Freud’s findings that irritants generate life. Primitive cells kept in a solution, perfect in temperature and nourishment, slowly die in contentment; but if an irritating agent is added to the liquid they become active and multiply. …”

On the importance of being periodically uncomfortable in order to stimulate our intellect.

“… Recently I came across this statement in the Illuminating Engineering Society’s Report of the Committee on Art Gallery Lighting: “Today any interior (museum) gallery can be artificially lighted to better effect than is possible by daylight; and, in addition, it can always reveal each item in its best aspect, which is only a fleeting occurrence under natural lighting.” A fleeting occurrence! Here, I believe, is the fallacy; for the best available artificial light trying to bring out all the advantages of an exhibit is, nevertheless, static. It does not change. Natural light, as it changes continuously, is alive and dynamic. The “fleeting occurrence” caused by the change of light is just what we need, for every object seen in the contrast of changing daylight gives a different impression each time. …”

The peculiar strengths of variable natural lighting.

“… The architect of the future should create through his work an original, constructive expression of the spiritual and material needs of human life, thus renewing the human spirit instead of rehearsing thought and action of former times. He should act as a co-ordinating organizer of broadest experience who, starting from social conceptions of life, succeeds in integrating thought and feeling, bringing purpose and form to harmony. …”

I very much agree, but a creative artist ought also be in command of what preceded his work. Only then could he propose a better alternative through his artistic creativity.

“… In music a composer still uses a musical key to make his composition understood. Within the framework of only twelve notes the greatest music has been created. Limitation obviously makes the creative mind inventive. …”

The positive impact of limitations on creativity.

“… The worst of all of these was that modern architecture became fashionable in several countries! Imitation, snobbery and mediocrity have distorted the fundamentals of truth and simplicity on which this renaissance was based. …”

Even in the year 1934 as modernism in architecture was just picking up speed, stylistic imitators of simplicity have began to emerge. Fast forward to today and one could see that 90% or modern architecture is just a mere stylistic emulation of exterior optics with no real meaning under the surface.

Above you may see one of Walter Gropius‘s initial buildings with its aesthetic emphasis on function, built between 1912-14.

“… Accordingly, the student needs the real thing, not buildings in disguise. So long as we do not ask him to go about in period clothes, it seems absurd to build college buildings in pseudo-period design. How can we expect our students to become bold and fearless in thought and action if we encase them timidly in sentimental shrines, feigning a culture which has long since disappeared? …”

On the governing design principles to be employed in campus planning. Gropius is not a fan of the long tradition of nostalgic architectural styles in campus design. Postulating that the design of the buildings where a student of modern architecture would be educated ought also be built by modern principles.

“… There is no copying to be found in order to preserve an external “cosmetic” uniformity. Unity was expressed by adherence to the given spatial order of existing buildings, not by imitating their veneers; exterior conformity was never mandatory in the past. Only our esthetic preoccupation with bygone periods has forced the “classical” façade on hundreds of college buildings built in the industrial age. …”

According to Mr. Gropius, in order to be contextual, one has to first of all be in total understanding of the given urban pattern of the context as opposed to emulating building surfaces of the past. Playing the urban game in footprint/plan will suffice according to him. Let the architecture be inventive itself without being restricted by the past.

“… The external embellishments of a building were designed mainly to outdo those of the neighboring building instead of being developed as a type fit to be used repeatedly as a unit in an organic neighborhood pattern. …”

The middle eastern problem of today in architecture.

“… The American Institute of Architects at its 1949 convention added to the mandatory rules of the Institute a new paragraph which reads:

“An architect may not engage directly or indirectly in building contracting.”

I have very great doubts about the wisdom of this rule which would perpetuate the separation of design and construc-tion. …”

Design and Construction in architectural practice ought never be distanced from each other, for the two fields have been married since the birth of the profession. If done carefully, being a developer and an architect is very much possible, given the circumstances of building politics today.

“… I do not mean that we architects should docilely accept the client’s views. We have to lead him into a conception which we must form to fit his needs. If he calls on us to fulfill some whims and fancies of his which do not make sense, we have to find out what real need may be behind these vague dreams of his and try to lead him in a con-sistent, over-all approach. …”

Gropius’ optimistic views on working with clients who may not know how to articulate their programmatic needs.

“… But the attempt to classify and thereby to freeze living art and architecture, while it is still in the formative stage, into a “style” or “ism” is more likely to stifle than to stimulate creative activity. …”

Why we should never attempt to label the predominant architectural thinking of today, while still in its fermentation processes. Better to leave that job for future historians.

“… The body called “society” is an indivisible entity which cannot function when some of its parts are not integrated or are being neglected; and when it does not function properly it will sicken. …”

“… our modern civic diseases: irresponsibility, deterioration of social contact, amorphous growth without coherence or distinctive form. …”

Sounds familiar ?

“… Disregarding some few secluded hermits, man is a gregarious animal whose growth is always accelerated and improved by life in a healthy com-munity. The reciprocal influence of individuals on each other is as essential to mental development as food is to the body. Left alone, without neighborly contact, the citizen’s mind is dulled, its growth stunted. …”

Pingback: A Proposal On The Revival of Gardening and Parks | Şahin Kaya Arıkoğlu

Pingback: A Proposal on The Revitalization of Parks and Gardening – Arikoglu Architecture Urban Design Construction and Interiors

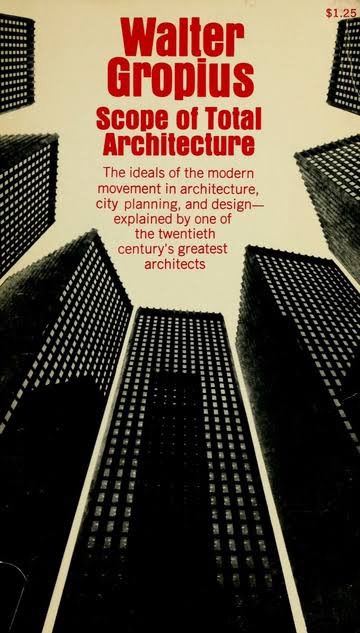

Scope of Total Architecture by Walter Gropius. It discusses Gropius’s opposition to the idea of an international architectural style. The author, Şahin Kaya Arıkoğlu, initially thought Gropius advocated for such a style based on his readings of other sources. However, after reading Gropius’s book, Arıkoğlu learned that Gropius in fact believed that architecture should be designed according to the specific context. Gropius argues that using new technologies should serve a humanist agenda.

LikeLike

Pingback: A Proposal On The Revitalization of Gardening and Parks – Arikoglu Architecture Urban Design Construction and Interiors