Since I began immersing myself in the works of acclaimed authors, I have observed significant voluntary changes in my internal thought processes. When I read multiple works by a single author whose style resonates deeply with me, I notice that my inner dialogue occasionally adopts the tone and perspective of that author. Including his point of view when needed. This shift is particularly noticeable when I reflect on my own intentions and actions, as I find myself evaluating decisions through the lens of personal benefit (advantageousness1) and moral integrity (Duty2). If a plan does not meet my internal moral standards, I promptly discard it and continue on hypothesizing different scenarios with better moral outcomes to reach a plan3 decision that is close to perfect.

Moreover, As I assess my decisions, I often invoke the insights of the authors I have recently read. I ponder questions such as, “What would they have done in my situation?” For instance, I might contemplate how Emperor Marcus Aurelius would respond if faced with a selfish neighbor who obstructed his parking space. By imaginatively integrating the voices and perspectives of these authors into my decision-making process, I strive to make more thoughtful and principled choices in my life. Hence, this may be considered as an additional rationale for which I consistently advise my junior colleagues to curtail mindless television and social media consumption and, instead, immerse themselves in reading books at the earliest opportunity they get.

The mind, I’ve come to realize, is not governed by a singular voice. Instead, it is shaped by multiple perspectives, especially as we engage with more intellectually stimulating works. The ideas of strong-minded authors enhance our inner discussions, adding layers of critical thought and alternative opinions, which we can distill and sort out until arriving to the most favorable hypotheses. Consequently, our actions are persistently evaluated by these internal voices, underscoring the necessity of ensuring that justice and morality guide our endeavors.4 As a secondary effect, these newly internalized voices often assume the role of judges, scrutinizing our actions and, if they disapprove, withdrawing from us and shaming us, which can lead to feelings of guilt, affecting our neurological well-being. Therefore, it is crucial to be discerning about which authors and stories we choose to read. We must avoid incorporating toxic or weak perspectives into our internal dialogue by selecting authors whose works align with our values and contribute positively to our inner discourse.

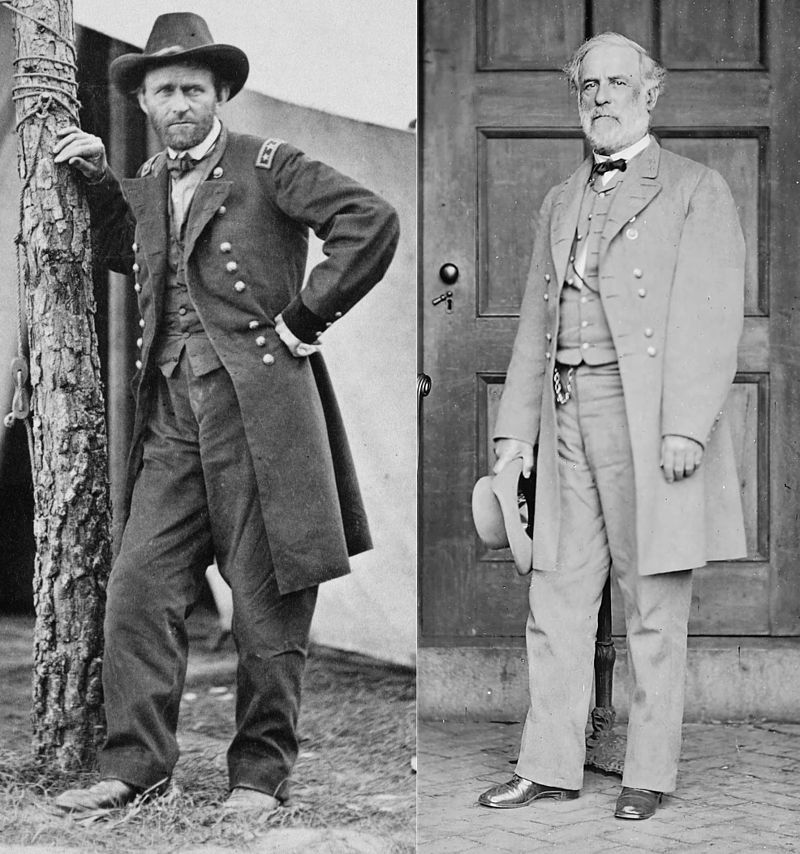

Take, for example, Ulysses S. Grant during the American Civil War. Grant possessed a strategic advantage over Confederate General Robert E. Lee, not just in military terms but morally as well. While Lee, despite his brilliance and dedication, was deeply invested in the protection of Virginia—particularly after his marriage into the Custis family, which tied him to Mount Vernon and the other Custis estates in Virginia—this focus may have detracted from his focus on the larger picture and strategy of the Confederate cause. Moreover, General Lee is noted for his opposition to slavery; in other words, he was a Confederate general whose personal ideologies were at odds with the pro-slavery principles of the Confederacy. Were his internal deliberations, over which one rarely has no complete control over, convincing him that his cause with the Confederates was fundamentally flawed? Might this internal conflict have contributed to his inability to secure a decisive victory during the Overland Campaign?5

Grant, by contrast, demonstrated a deeper conviction. During the Overland Campaign, after the initial setbacks in the Wilderness, Grant chose not to retreat but to press forward despite the odds. This determination can be attributed to a strong moral compass guiding his actions, an internal voice and discussion assuring him that his cause was just. This underscores the importance of acting with righteousness, as having moral conviction strengthens our resolve in the face of challenges. The warrior king Charles XII of Sweden, like Ulysses S. Grant during the Civil War, mobilized his armies for the Great Northern European campaign driven by similar inner convictions. Based on historical accounts, he was clearly not the initial aggressor in the Great Northern War (1700–1721), Thus, he was endowed with exceptional mental capabilities of bravery and prowess in confronting his adversaries, a formidable coalition of European powers6.

Footnotes:

- Recommended reading in this topic: De Officiis (On Duties) by Marcus Tullius Cicero 44BC

- Recommended reading in this topic: De Officiis (On Duties) by Marcus Tullius Cicero 44BC

- For further reading on the subject of planning, please read through my essay on the importance of having a plan, published in September 2024.

- For further reading on this subject of inner discussions, please read through my essay on “The Dialogue Within“, published in July 2020.

- Recommended reading to better understand the nature of the civil War, General Ulysseus Grant and General Robert E. Lee: Grant, By Ron Chernow

- Recommended reading to better understand the Great Northern War and the main characters involved with it, Charles XII and Peter The Great: Peter The Great, His Life and World, by Robert K. Massie

Image Credits:

a) Original uploader was Hlj at en.wikipedia (Original text: Montage by Hal Jespersen) – Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons. Original images from the US Archives civil war photos: 32. Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant standing by a tree in front of a tent, Cold Harbor, Va., June 1864. 111-B-36. 145. Lee, Gen. Robert E.; full-length, standing, April 1865. Photographed by Mathew B. Brady. 111-B-1564.

Pingback: Book Review: 12 Rules For Life, An Antidote to Chaos, by Jordan B. Peterson | Şahin Kaya Arıkoğlu